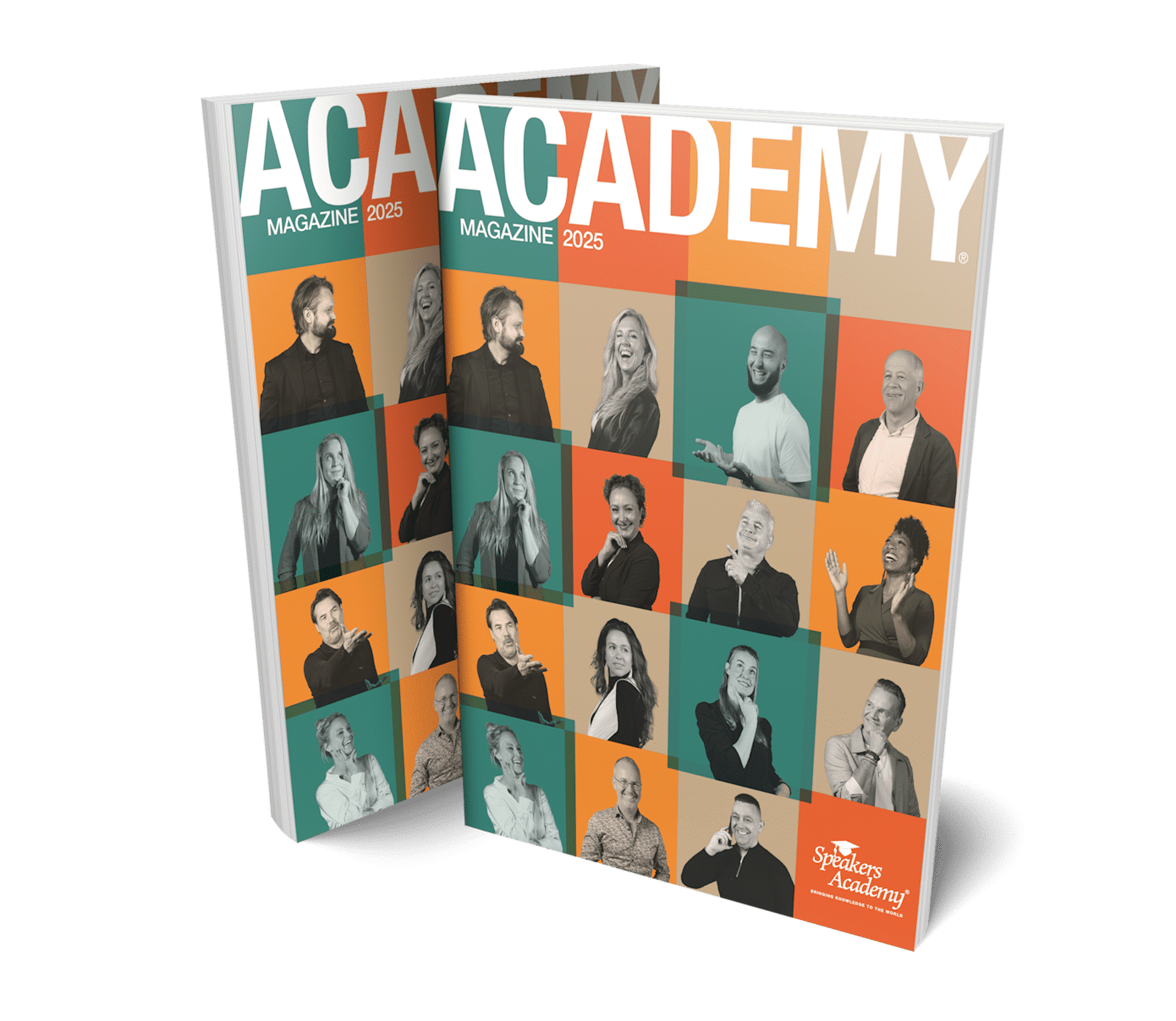

De sprekers verbonden aan Speakers Academy zijn allen gespecialiseerd in een of meerdere onderwerpen. Daardoor kunnen wij altijd bekende, inspirerende of motiverende sprekers of dagvoorzitters matchen aan jouw event. Naast het boeken van sprekers en dagvoorzitters kan Speakers Academy ook helpen met organiseren van een workshop, webinar of een boardroom sessie.