Developing the most impactful behaviours

Every team aspires to stronger ownership and more proactive behaviour, yet many leaders struggle to understand why certain behaviours simply don’t take hold. The gap between what is expected and what people actually do often has less to do with skills or intentions, and more with the unseen barriers that shape behaviour.

Roderick Gottgens

Organizational Behavior SpecialistWhere it gets stuck

Imagine you’re leading a team. “Taking responsibility” is one of those themes you keep coming back to. When things go wrong, need extra attention, or could be done better, you expect your people to step up, speak up, own their mistakes, give feedback to each other and, occasionally, even to you.

But you already know what happens: it rarely works that smoothly. Not everyone seems to take the same level of responsibility. Some hesitate to give feedback, others remain silent, and only a few dare to question your decisions. It’s not that there’s visible tension in the team, but despite your efforts to create an open culture, the gap between what people believe taking responsibility means and how they act is significant.

This is one of the most common dynamics within teams and organisations. In fact, I can’t recall a single team where it doesn’t play out. Capable, intelligent people, but each operating at very different “behavioural levels.” For a leader, this can be deeply frustrating. You want everyone performing at their best. “Taking responsibility” (or “showing ownership”) is a core value, and you work hard to encourage it. Yet progress often feels slow and inconsistent.

The perceived difficulty of behaviour

Here’s the kicker. That frustration often stems from a single question most teams never ask:

“How difficult does it feel to show the behaviour we expect?”

Let me explain.

Whether someone shows a certain behaviour, rarely depends on circumstances, context or situation alone. Of course, factors like company culture, market conditions, workload, time pressure, and team dynamics all play a role. But there’s something subtler at work: the perceived difficulty of behaviour. The inner barrier a person feels between knowing what to do and actually doing it.

Behavioural science has explored this in depth. Several well-known theories (such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour, Social Cognitive Theory, and Campbell’s Paradigm) show that behaviour isn’t just shaped by circumstances, context or situation, but maybe even more by how people perceive the ease or difficulty of acting. Some actions require more mental energy, courage, or conviction than others. And the harder a behaviour feels, the less likely someone is to do it. Even when they know exactly what’s expected.

Take giving feedback, as another example. For one person, giving feedback might feel like a small step; for another, it feels like jumping off a cliff. The rules haven’t changed, but the psychological barrier has. That perceived difficulty explains why some team members engage easily while others hold back.

Behavioural difficulty, then, is like a hidden scale that determines which steps people dare to take. It’s the bridge between intention and action. When you make that difficulty visible, you start to see which behaviours are low barrier, thus perceived as easy to perform, and which ones demand greater support, trust, role modelling or even training, and thus perceived as hard(er) to perform. Because leadership isn’t only about defining what behaviour you want to see, but also about understanding which barrier someone must cross to get there.

The Behaviour Ladder

And that’s where the game of leading your team or organization begins: by understanding where someone currently stands, and what their next achievable step might be. Not by pushing or pulling, but by making the pathway toward desired behaviour visible.

In the behavioural research we conduct for organizations, we use what we call The Behaviour Ladder.

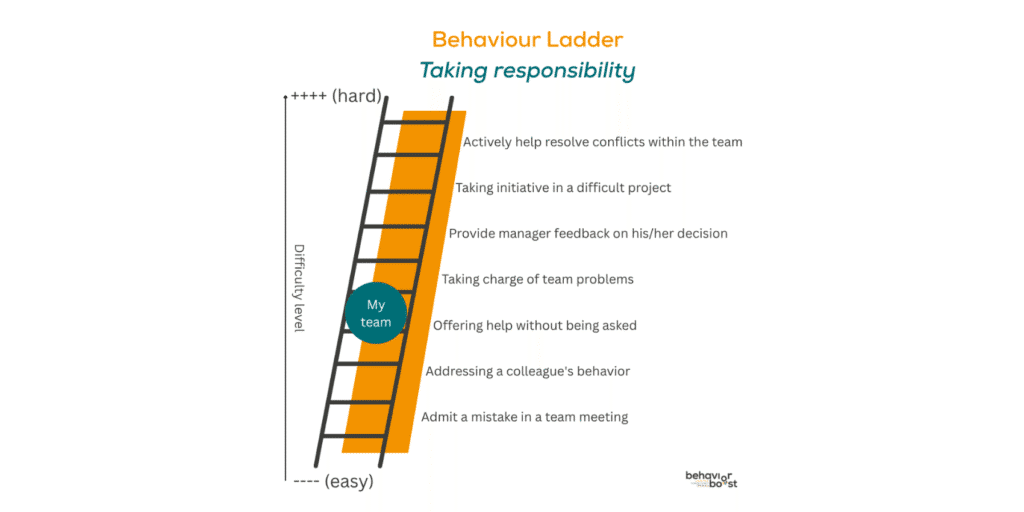

The Behaviour Ladder clarifies which specific actions make up an attitude like “taking responsibility” or “showing ownership”. It then arranges those actions from easier, low-barrier behaviours to more challenging ones that require courage or persistence. Visualising those behaviours as steps on a ladder reveals the natural progression of growth.

As a leader, this helps you see where your team members are: which actions feel natural, and which still feel daunting. That insight highlights where energy flows easily, and where it gets stuck.

The power of the ladder lies in its concreteness. You’re no longer talking in vague terms about “more ownership” or “greater accountability”. You can literally point to the next logical step. Because meaningful behavioural change rarely happens in big leaps. It happens one step at a time, gradually moving closer to the desired mindset.

Here’s an example of what such a ladder might look like for the attitude “taking responsibility.”

From confronting to developing behaviour

With such a ladder in hand, your role as a leader shifts. From confronting people about their behaviour to developing it. You no longer just see who is “doing it right” or “falling short”, but where each person is in their developmental journey. That makes conversations far more constructive: together, you can explore what someone needs to climb one step higher. Sometimes that’s more trust, sometimes a role model, sometimes training and sometimes simply the freedom to practise without fear of judgment.

At the team level, the ladder helps reveal collective patterns: where the group tends to get stuck, and which next step requires shared attention or leadership intervention. It turns behavioural development into something measurable and discussable. Not as an evaluation, but as a growth path.

Because, ultimately, that’s what, in my opinion, leading people is all about: not demanding perfect behaviour, but systematically lowering the barriers that stand in the way of growth.

In closing

Most leaders want their people to take more responsibility, speak up, and show initiative. But few ever ask the question: how difficult does that actually feel for them? Once you start seeing behaviour through that lens, everything changes. You stop viewing it as right or wrong, but start seeing it as something that develops, step by step, over psychological barriers.

And perhaps that’s the core lesson of the Behaviour Ladder: meaningful behavioural change doesn’t start with others. It starts with you, the leader. With your willingness to understand where the real barriers lie, instead of simply pushing harder for people to cross them.

Roderick Gottgens

Organizational Behavior SpecialistRoderick Göttgens makes you realize what you already know: Results are driven by actions. Actions...

Request quote View profile